domingo, 31 de julio de 2016

sábado, 30 de julio de 2016

Trabaja por la Aviación

"Por lo general lo que conduce y arrastra al mundo no son las máquinas sino que las ideas. Trabaja pues, por entregar tus experiencias por una aviación mas prospera y segura."

jueves, 28 de julio de 2016

martes, 26 de julio de 2016

lunes, 25 de julio de 2016

domingo, 24 de julio de 2016

viernes, 22 de julio de 2016

jueves, 21 de julio de 2016

miércoles, 20 de julio de 2016

178 seconds

If you’re ever tempted to take off in marginal

weather and have no instrument training, read

this article first before you go. If you decide to go

anyway and lose visual contact, start counting

down from 178 seconds.

How long can a pilot who has no instrument

training expect to live after he flies into bad

weather and loses visual contact? Researchers

at the University of Illinois found the answer to

this question. Twenty students “guinea pigs” flew

into simulated instrument weather, and all went

into graveyard spirals or rollercoasters. The

outcome differed in only one respect; the time

required until control was lost.

The interval ranged

from 480 seconds to 20 seconds. The average

time was 178 seconds—two seconds short of

three minutes.

Here’s the fatal scenario...

The sky is overcast and the visibility poor. That

reported 5-mile visibility looks more like two,

and you can’t judge the height of the overcast.

Your altimeter says you’re at 1500 but your map

tells you there’s local terrain as high as 1200 feet.

There might even be a tower nearby because

you’re not sure just how far off course you are.

But you’ve flown into worse weather than this,

so you press on.

You find yourself unconsciously easing back just a

bit on the controls to clear those non-too-imaginary

towers. With no warning, you’re in the soup. You

peer so hard into the milky white mist that your

eyes hurt. You fight the feeling in your stomach.

You swallow, only to find your mouth dry. Now you

realize you should have waited for better weather.

The appointment was important—but not that

important. Somewhere, a voice is saying “You’ve

had it—it’s all over!”.

You now have 178 seconds to live. Your aircraft

feels in an even keel but your compass turns

slowly. You push a little rudder and add a little

pressure on the controls to stop the turn but this

feels unnatural and you return the controls to their

original position. This feels better but your compass

in now turning a little faster and your airspeed is

increasing slightly. You scan your instrument panel

for help but what you see looks somewhat unfamiliar.

You’re sure this is just a bad spot. You’ll

break out in a few minutes. (But you don’t have

several minutes left...)

You now have 100 seconds to live. You glance at

your altimeter and are shocked to see it unwinding.

You’re already down to 1200 feet. Instinctively,

you pull back on the controls but the altimeter

still unwinds. The engine is into the red—and the

airspeed, nearly so.

You have 45 seconds to live. Now you’re sweating

and shaking. There must be something wrong with

the controls; pulling back only moves that airspeed

indicator further into the red. You can hear the wind

tearing at the aircraft.

You have 10 seconds to live. Suddenly, you see the

ground. The trees rush up at you. You can see the

horizon if you turn your head far enough but it’s at

an unusual angle—you’re almost inverted. You

open your mouth to scream but...

...you have no seconds left

lunes, 18 de julio de 2016

Aliadas en Aviación

"La perseverancia y el conocimiento en Aviación, son por cierto dos grandes aliadas y resultan ser juntas las mejores armas que se tiene para poder salir adelante en el proyecto de estudio".

JMDF

JMDF

sábado, 16 de julio de 2016

Perfil de examen DGAC en la web

PERFILES PARA EXAMEN DE LA HABILITACIÓN VUELO POR INSTRUMENTOS EN ENTRENADOR SINTÉTICO DE VUELO PARA AVIACIÓN GENERAL.

- Perfil Simulador SCAT (pdf 85kb)

- Perfil Simulador SCCI (pdf 84kb)

- Perfil Simulador SCDA (pdf 83kb)

- Perfil Simulador SCEL (pdf 84kb)

- Perfil Simulador SCIE (pdf 84kb)

- Perfil Simulador SCIP (pdf 84kb)

- Perfil Simulador SCPQ (pdf 84kb)

- Perfil Simulador SCQP (pdf 84kb)

- Perfil Simulador SCSN-A (pdf 84kb)

- Perfil Simulador SCSN-B (pdf 84kb)

- Perfil Simulador SCSN-C (pdf 84kb)

- Perfil Simulador SCTE (pdf 84kb)

- Perfil Simulador SCVD (pdf 85kb)

- Perfil Simulador SCVM (pdf 84kb)

jueves, 14 de julio de 2016

AD Peldehue

Aeródromo de Peldehue absorberá el 30% del trafico de Tobalaba y obras se inician en dos meses.

Las operaciones del antiguo recinto, ubicado en la comuna de La Reina, fueron restringidas en 2008 tras el accidente aéreo donde fallecieron 13 personas.

Autoridades esperan que en no más de dos meses parta la construcción del nuevo aeródromo en Peldehue .

El ministro de Obras Publicas, Alberto Undurraga, firmó hoy la resolución que da inicio definitivo a la construcción del nuevo Aeródromo de Peldehue, que es el resultado de un convenio entre la Dirección de Aeropuertos del MOP y el Ejército.

La construcción permitirá absorber parte del tráfico del recinto ubicado en Tobalaba, el cual se restringió luego del accidente de 2008 en que murieron 13 personas. "Esperamos que el proyecto salga inmediatamente de Contraloría, porque va a ingresar la próxima semana la adjudicación, para decir que empezamos el camino sin retorno para tener la nueva pista, el nuevo aeródromo en en la región Metropolitana", comentó el ministro Undurraga.

El nuevo recinto estará ubicado a 30 kilómetros de Santiago en la comuna de Colina y será el primer aeródromo público, administrado por la Dirección Aeronáutica.

El Jefe del Comando de Bienestar del Ejército, General de Brigada Claudio Hernández, aseguró que tendrá una función mixta porque "va a facilitar operaciones propias del Ejercito, como instrucción y entrenamiento, además de una proyección estratégica importante desde el núcleo central del país".

Respecto a qué pasará con el Aeródromo Tobalaba, el director general de Aeronáutica Civil, Víctor Villalobos, informó que las operaciones seguirán disminuyendo.

"Desde 2008 a la fecha, de 79 mil operaciones ha bajado a 45 mil. Se presume que vamos a bajar un 30% más",

miércoles, 13 de julio de 2016

martes, 12 de julio de 2016

Qatar Airlines entrará a la propiedad de Latam Airlines

Qatar Airlines tomará hasta 10% de la propiedad de Latam Airlines mediante un aumento de capital. El precio de suscripción será de US$ 10 por acción. Se cree que esto será bueno para Latam que mejorará sus ratios de endeudamiento y quedará en mejor pie frente a sus competidores, dado que era el único que no tenía parte de su propiedad en manos de alguna gran aerolínea extranjera.

lunes, 11 de julio de 2016

178 Seconds to Live

Author Unknown

How long can a licensed VFR pilot who has little or no instrument training expect to live after he flies into bad weather and loses visual contact? In 1991 researchers at the University of Illinois did some tests and came up with some very interesting data. Twenty VFR pilot "guinea pigs" flew into simulated instrument weather, and all went into graveyard spirals or roller coasters. The outcome differed in only one respect - the time required until control was lost. The interval ranged from 480 seconds to 20 seconds. The average time was 178 seconds -- two seconds short of three minutes.

Here's the fatal scenario. . . . . . . The sky is overcast and the visibility is poor. That reported five mile visibility looks more like two, and you can't judge the height of the overcast. Your altimeter tells you that you are at 5500 feet but your map tells you that there's local terrain as high as 3200 feet. There might be a tower nearby because you're not sure how far off course you are so you press on.

You find yourself unconsciously easing back just a bit on the controls to clear those towers. With no warning, you're in the soup. You peer so hard into the milky white mist that your eyes hurt. You fight the feelings in your stomach that tell you're banked left, then right! You try to swallow, only to find your mouth dry. Now you realize you should have waited for better weather. The appointment was important, but not all that important. Somewhere a voice is saying, "You've had it -- it's all over!" You've only referred to you instruments in the past and have never relied on them. You're sure that this is just a bad spot and you'll break out in a few minutes. The problem is that you don't have a few minutes left.

You now have 178 seconds to live.

Your aircraft "feels" on even keel but your compass turns slowly. You push a little rudder and add a little pressure on the controls to stop the turn but this feels unnatural and you return the controls to their original position. This feels better but now your compass is turning a little faster and your airspeed is increasing slightly. You scan your instruments for help but what you see looks somewhat unfamiliar. You are confused so you assume the instruments must be too. You are now experiencing full blown Spatial Disorientation. Up feels like down and left feels like right. You feel like you are straight and level again but you're not. The spiral continues.

You now have 100 seconds to live.

You glance at your altimeter and you are shocked to see it unwinding. You're already down to 3000 feet. Instinctively, you pull back on the controls but the altimeter still unwinds. You don't realize that you are in a graveyard spiral and it only gets worse. Your plane is almost sideways you're just tightening the turn by pulling back on the yoke, but all you can see is that altimeter going lower, lower, lower. The engine is into the red and growling and the airspeed is dangerously high. The sound of the air passing by begins to resemble a scream.

You now have 45 seconds to live.

Now you're sweating and shaking. There must be something wrong with the controls; pulling back only moves the airspeed indicator further into the red. It's supposed to do the opposite! You can hear the wind tearing at the aircraft. Rivets are popping as the load on the wings and tail far exceeds design specifications. 1800, 1500, 1100 feet...... down you go.

You now have 10 seconds to live.

Suddenly you see the ground. The trees rush up at you. You can now see the horizon if you turn your head far enough but it's at a weird angle -- you're almost inverted! You open your mouth to scream but. . . . . . Your time is up!

UNUSUAL ATTITUDE PREVENTION: LEVEL THE WINGS, CHECK THE AIRSPEED, CHECK THE ALTITUDE, AND PUT THE NOSE ON THE HORIZON! REDUCE THE LOAD ON YOUR WINGS: LEVEL THE WINGS! GET YOUR EYES OFF OF THE ALTIMETER AND LOOK AT YOUR ATTITUDE INDICATOR AND TURN COORDINATOR. THEN LEVEL THE WINGS!

For a discussion of this research study, see 178 Seconds Dissected by Paul McGhee

domingo, 10 de julio de 2016

SARSEV

SARSEV: BOLETÍN N° 14 DE SEGURIDAD OPERACIONAL

|

| Esta versión incluye casos de pilotos pero el modelo es aplicable a todo el personal aeronáutico. Cada caso incluye un análisis TEM y recomendaciones operativas. |

"Mi experiencia en beneficio de todos", ha sido la consigna que ha caracterizado a SARSEV (Sistema Anónimo de Reportes de Seguridad de Vuelo) desde su puesta en marcha en el año 2010 y que se ve plasmada en los múltiples casos y análisis que se presentan en cada publicación de sus boletines.

El Boletín N° 14, trata sobre el modelo de Gestión de Amenazas y Errores (“Threat Error Management” o TEM, por sus siglas en inglés), aplicándolo a situaciones reportadas a SARSEV por pilotos. TEM es un modelo diseñado por especialistas en Factores Humanos de la Universidad de Texas, USA, que permite afrontar las complejidades inherentes a sistemas altamente técnicos, en los que está presente el ser humano, y por ende, el error.

En el modelo TEM, los errores de otros son concebidos como amenazas para la seguridad de mi operación y en este boletín, cada caso incluye un análisis TEM y recomendaciones operativas.

Desde SARSEV señalan que este modelo refuerza y apoya una cultura positiva de la seguridad operacional, tal como la que se promueve a través de este sistema. El constante análisis y la difusión de las experiencias de pilotos, personal ATS, de mantenimiento y tripulantes de cabina, permite aprender, como sistema, de los errores de otros y evitar la ocurrencia de accidentes.

También, SARSEV hace un llamado a reportar. Enfatizan que cada experiencia sirve y puede ser una valiosa herramienta de prevención.

A través de las redes sociales, permanente están recibiendo reportes y además, publican información de seguridad operacional e información actualizada de las actividades y de las publicaciones de nuevos boletines.

Ingresa a Twitter: @SARSEVChile, Facebook: Sarsev Chile

viernes, 8 de julio de 2016

TRABAJADORES DE LAN DENUNCIARON INTERFERENCIA DE LA DGAC EN LA LEY LABORAL

Publicado el 06 de julio del 2016

Ante la Comisión de Trabajo de la Cámara, los sindicatos de tripulantes de cabina de la compañía aérea explicaron que la Dirección General de Aeronáutica Civil superó la normativa vigente relativa a la extensión de jornada laboral, afectando con ello los derechos de los funcionarios. Los legisladores criticaron la interferencia y acordaron enviar oficios a las instituciones relacionadas, de modo de hacer un seguimiento del caso.

En una interferencia en la ley laboral que vendría afectando los derechos de los trabajadores de aerolíneas naciones y, particularmente, sus horas de descanso, estaría incurriendo la Dirección General de Aeronáutica Civil (DGAC), según denunciaron anoche ante la Comisión de Trabajo de la Cámara, los sindicatos de tripulantes de cabina de Lanexpress y Lan.

Ambos grupos de representantes coincidieron en criticar la intromisión de la DGAC, la que superaría la ley vigente y los dictámenes de la Dirección del Trabajo relativa a las causales por las cuales es posible extender la jornada laboral.

Según explicaron, la normativa indica tres causales específicas que permiten una extensión de la jornada de 12 horas: causas meteorológicas, por emergencia médica o por necesidad de mantenimiento de la aeronave. La DGAC, precisaron, agregó una cuarta excepción, de carácter ambiguo y genérico, que permite extender la jornada cuando el capitán lo decida por razones de seguridad.

Criticaron que, además, la DGAC traspasó un dictamen de la Dirección del Trabajo que especifica el ámbito de aplicación de la extensión de jornada. Así, mientras la primera remarca que la excepción se aplica solo en el último vuelo de una serie de vuelos, la segunda la aplica para todo un trayecto.

Asimismo, refutaron que la DGAC intervenga en la definición de la cantidad mínima de tripulantes de cabina respecto del número de asientos, transgrediendo la norma específica; y que haya autorizado a la empresa aérea a extender la jornada laboral de los trabajadores en casos específicos (terremoto y apagón de Santiago), sin tomar las necesarias precauciones de seguridad sobre la materia.

"¿Cuáles son los límites que la DGAC tiene? ¿Hasta dónde llega su competencia? Para nosotros la DGAC tiene que velar por la seguridad de los vuelos y dejar a la Dirección del Trabajo que haga su tarea en cuanto a la jornada laboral", enfatizó en su presentación Silka Seitz, presidenta del sindicato de tripulantes de cabina de Lanexpress

En la misma línea, Javier Brinzo, tesorero de dicha agrupación, sostuvo que la DGAC se está tomando atribuciones que no le corresponden, poniendo en riesgo, por fatiga, la seguridad de los vuelos, de las tripulaciones, de los pilotos y de los pasajeros, todo bajo la excusa de fiscalizar y regular. Además, afirmó que esta situación favorece a la empresa, ya que ha adoptado la postura de la DGAC, desconociendo con ello los dictámenes de la Dirección del Trabajo.

Arlette Gay, representante del sindicato de tripulantes de cabina de Lan, quien estuvo acompañada en su presentación por la presidenta de la agrupación, Claudia Bobadilla, resaltó el logro que significó para los trabajadores del sector la constitución de un estatuto especial y remarcó que no tienen problemas con la actual normativa, salvo algunas diferencias que se están resolviendo por la vía de la Dirección del Trabajo.

Sin embargo, coincidió con los anteriores en que el problema está dado por la intromisión de la DGAC en materia laboral, particularmente del Departamento de Seguridad Operacional y por el estrecho relacionamiento que tiene esta unidad con las empresas operadoras.

Oficios y opiniones

Al término de la sesión, los diputados Tucapel Jiménez (PPD), presidente accidental de la Comisión, y Osvaldo Andrade (PS) reconocieron el problema planteado y anunciaron que, para analizar con mayor precisión el tema, se acordó oficiar tanto a la Dirección del Trabajo como a la DGAC para que expresen su opinión y para que, en el evento de que exista efectivamente una colisión de atribuciones, se pueda llegar a una solución, ya sea por la vía legislativa o administrativa.

El diputado Andrade dijo que, además, se encomendó a la Biblioteca del Congreso Nacional un estudio internacional comparado para conocer cómo otros países de similares características resolvieron la diferencia de competencia entre los entes reguladores (el del área de la seguridad aeronáutica y del ámbito laboral).

"Mi impresión es que hay una invasión de la DGAC en las competencias laborales y este no es el órgano destinado para eso, es la Dirección del Trabajo", planteó el legislador, reconociendo sí que hay un terreno que hay que mirar, cual es el de la fatiga de los trabajadores, como un tema asociado a la seguridad. En todo caso, estimó que el asunto puede resolverse con voluntad y rápidamente.

Asimismo, el diputado Andrade destacó que la normativa que hoy rige a los tripulantes de cabina fue objeto de una organización ramal, tripartita, que se hizo hace varios años atrás, que contó con el respaldo de la totalidad del Parlamento y que permitió la titularidad del sindicato para establecer pactos de adaptabilidad en materia de jornada.

jueves, 7 de julio de 2016

How The 4 Types Of Landing Gear Struts Work

05/26/2016

No matter how hard we all try, not every landing is perfect. But thanks to landing gear struts, even a not-so-perfect landing doesn't break your airplane into pieces.

There are 4 primary types of landing gear struts, and all of them are designed to help take the 'shock' out of your landing. Here's how they work.

Rigid Struts

Rigid struts were the original type of landing gear. The idea was simple: weld the wheels to the airframe. The problem was the imperfect landing; a hard touchdown meant the strong shock load transfer went directly into the airframe. And the pilot and passengers definitely felt it.

Soon after, aircraft engineers started putting inflatable tires on aircraft, and the air softened the impact load. While it wasn't a perfect solution, it definitely helped.

While you don't see them as often these days, you can still find rigid struts on the ramp. Almost all helicopters use them, in the form of metal skids attached to the frame of the helicopter.

Spring Steel Struts

One of the most common landing strut systems on general aviation aircraft is the spring steel strut. If you've ever flown (or ridden in) a Cessna, you know what it is. These aircraft use strong, flexible materials like steel, aluminum or composites to help absorb the impact of a landing.

As your plane touches down, the springs flex upward, dissipating and transferring the impact load to your airframe at rate that (hopefully) doesn't bend your plane. Spring steel is popular because it's mechanically simple, typically lightweight, and needs little to no maintenance. Plus, if you were like me when I was learning to fly, you know they can really take a beating.

Bungee Cords

Bungee cords are often found on tailwheel and backcountry airplanes. One of the most popular examples, and one you've probably seen, is the Piper Cub.

Bungee cords are just that - a series of elastic cords wrapped between the airframe and the flexible gear system, allowing the gear to transfer impact load to the aircraft at rate that doesn't hurt the plane. While some aircraft use a donut-type rubber cushion, most of them use lots of individual strands of elastic material to dissipate the shock, like the one pictured below.

Shock Struts

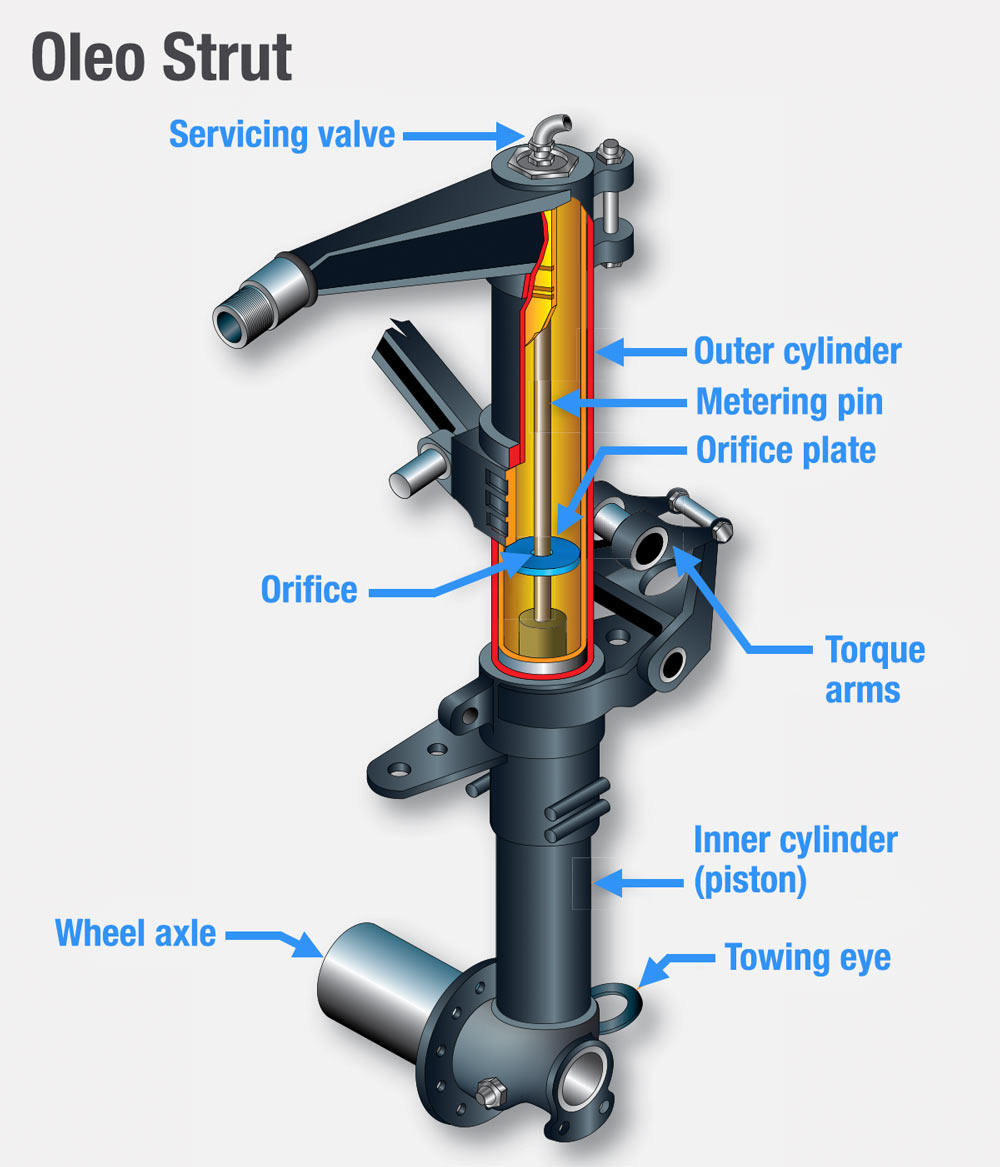

The last type of strut is the only one that is a true shock absorber. Shock struts, often called oleo or air/oil struts, use a combination of nitrogen (or sometimes compressed air) and hydraulic fluid to absorb and dissipate shock loads on landing. You can find them on some smaller aircraft, like the Piper Cherokee, but you most often find them on larger aircraft, like business jets and airliners.

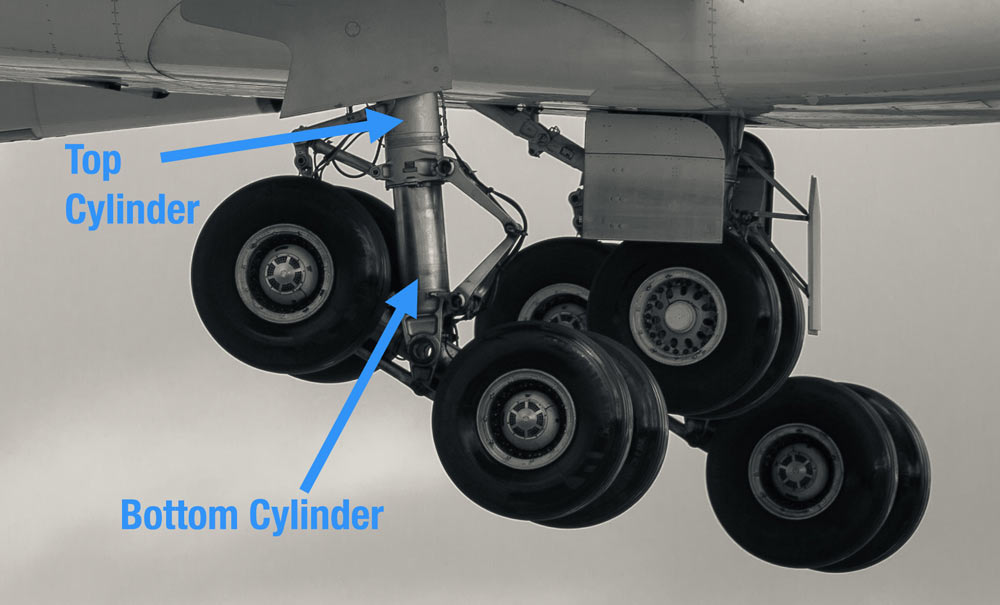

Shock struts use two telescoping cylinders, both of which are closed at the external ends. The top cylinder is attached to the aircraft, and the bottom cylinder is attached to the landing gear. The bottom cylinder, typically called the piston, can also freely slide in and out of the upper cylinder.

If you look at a cutaway of the two cylinders, what you almost always find is the bottom cylinder filled with hydraulic fluid, the top cylinder filled with nitrogen, and a small hole, called an orifice, connecting the two.

As you land, pressure from the wheels hitting the ground forces hydraulic fluid up through the orifice and into the top, nitrogen filled chamber. As the fluid moves through the hole (very quickly, by the way), it creates heat. And essentially, the kinetic energy of fast moving hydraulic fluid is transferred into thermal energy, and the shock of your touchdown is absorbed.

You can really see oleo struts in action when you watch airliners land. A perfect example was the Virgin Atlantic 747 that landed with one of its main gear up. The other three main gear struts took over and absorbed the landing, and you can see them compress on the touchdown.