|

03/14/2020

Have you ever seen your descent rate exceed 1,000 feet per minute on an instrument approach? Here's why you should take corrective action if it happens...

Follow A 1,000 FPM Descent Rate Limit

The FAA has published guidance on what it considers to be safe descent limits for instrument approaches. Here's what Chapter 4 of the IPH has to say, and what you should know to stay safe on your next IFR flight...

Operational experience and research have shown that a descent rate of greater than approximately 1,000 FPM is unacceptable during the final stages of an approach (below 1,000 feet AGL). This is due to a human perceptual limitation that is independent of the type of airplane or helicopter. Therefore, the operational practices and techniques must ensure that descent rates greater than 1,000 FPM are not permitted in either the instrument or visual portions of an approach and landing operation.

Simply put, sustained descent rates over 1,000 FPM are unstable on approach. Physically, your body cannot perceive and react to descent rates over 1,000 FPM adequately. In the instrument environment with low ceilings and few visual cues, this is especially important. Here's what else you should know...

Flying Non-Precision? This Is Why VDPs Are So Important...

According to the FAA, "for short runways, arriving at the MDA at the MAP when the MAP is located at the threshold may require a missed approach for some aircraft" (IPH 4-37).

Well, duh. When was the last time you flew at MDA to the MAP of a non-precision approach, at the last second caught the runway in-sight a few hundred feet below you, and landed? Probably never.

If you meet the three criteria below, you can land descend from MDA and land. Does that mean it's a good idea? Not always.

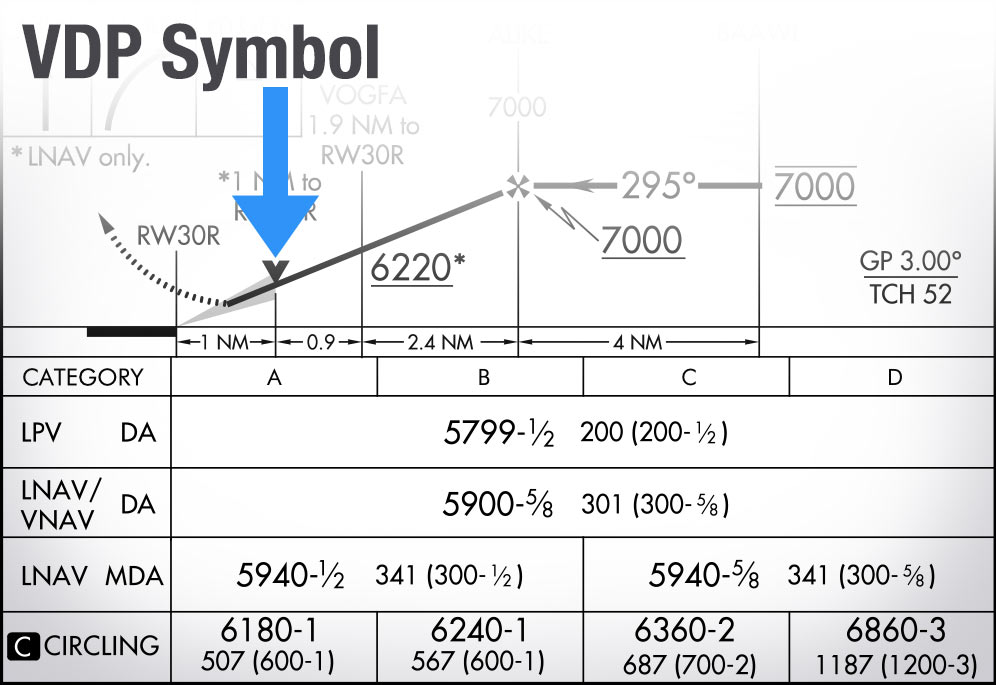

According to the AIM, "the VDP is a defined point on the final approach course of a non-precision straight-in approach procedure from which normal descent from the MDA to the runway touchdown point may be commenced." When you reach VDP, you'll typically be able to follow a 3-degree glide path to the runway, which is the same glide path as most precision approaches.

Beyond a normal 3-degree glide path, this will also ensure you fly a normal descent rate to the runway.

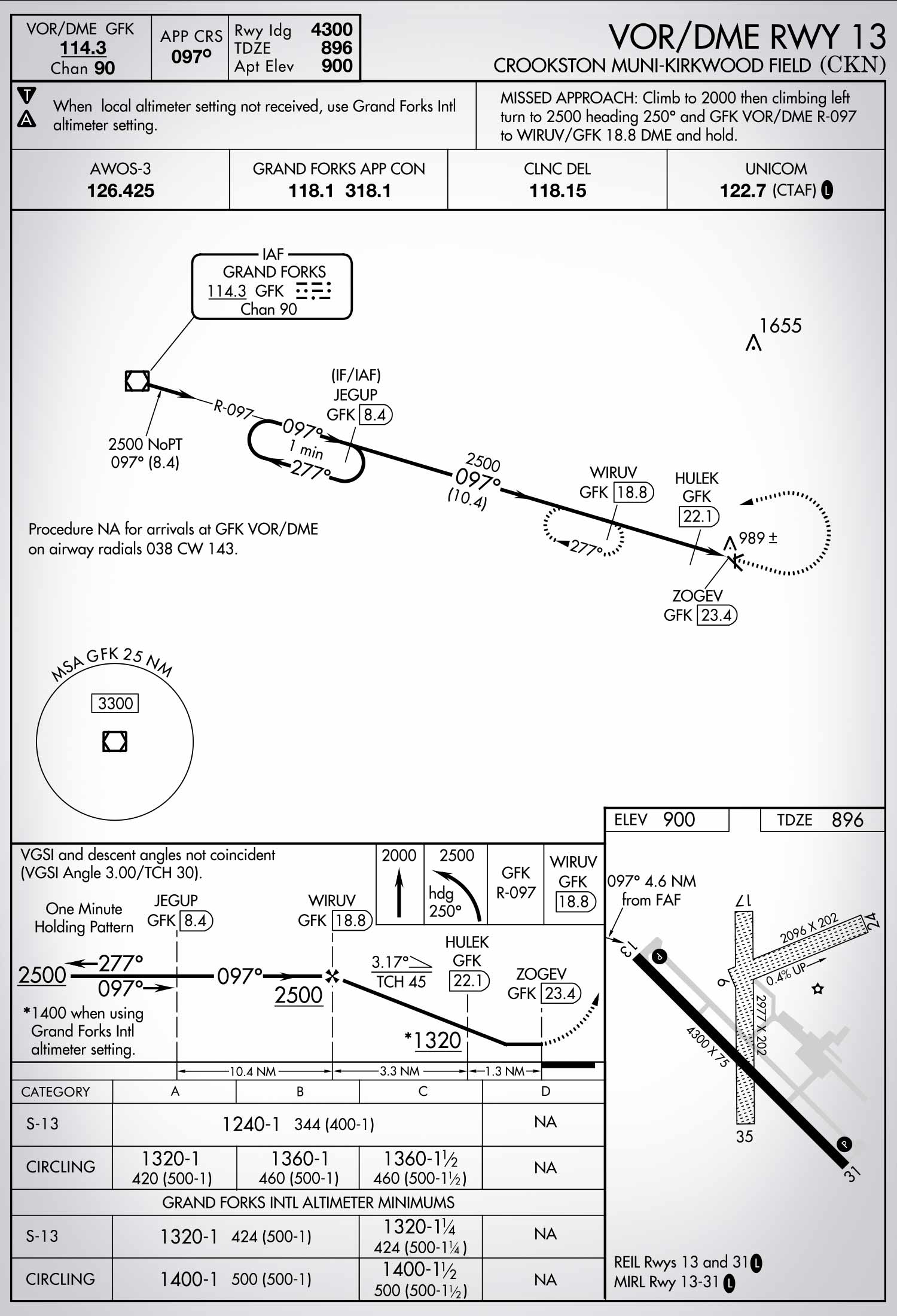

When instrument procedure designers survey land during the creation of an approach, they'll analyze what obstructions penetrate safety clearance tolerances. If obstructions are present, a VDP might be denied during the creation of the instrument approach. This is why you won't find a "V" published on every non-precision approach, like the image below.

If that's the case, you can use a rule-of-thumb to find the approximate distance where you would start a descent from MDA to the runway: Take the AGL value of the MDA and divide it by 300.

For example, on the Crookston (KCKN) VOR/DME Approach to Runway 13, the lowest MDA takes you to 344 feet above the TDZE. Divide this by 300, and you'll get 1.15, which is the approximate distance from the runway where you can start a 3-degree descent to the runway.

Anticipating Your Descent Rate

Click here to learn about two easy ways you can calculate your descent rate. If you're flying more than a 3-degree glidepath, or have a significantly high groundspeed due to a tailwind, you might find yourself getting close to the 1,000 FPM descent rate limit.

When Should You Go-Around?

At most airlines, continuously exceeding 1,000 FPM on an instrument approach is considered unstable. Momentary deviations are allowed, however. On some aircraft, if there is a "sink rate" aural warning, it can be corrected for by the pilot once. If the warning sounds again, an immediate missed approach must be flown.

In the general aviation world, you're usually flying a lot slower than an airliner on final approach. Generally speaking, this will keep your descent rate lower as well. If you start to push close to a 1,000 FPM descent rate, you're likely unstable. Consider going around and trying the apporach again.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario

Espero atento tus comentarios